Gastornis was also discovered in Wyoming but scientists confirm finding of fossils on Ellesmere island as bird thought to migrate during dark Arctic winters

A giant, flightless bird with a head the size of a horse’s roamed the Arctic 53m years ago when the icy wilderness was more like a swamp, scientists have confirmed.

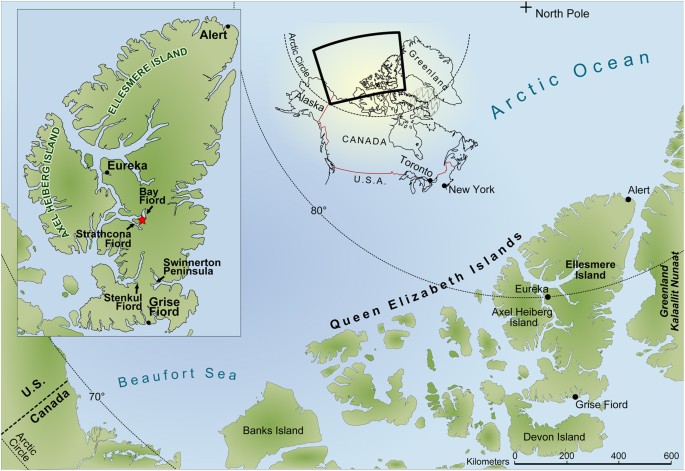

A joint study by American and Chinese institutions found that the massive beast, known as Gastornis, existed on what is now known as Ellesmere island, found above the Arctic circle. It’s estimated the bird was 6ft tall and weighed several hundred pounds.

The evidence for Gastornis’s presence in the Arctic comes from a single fossil toe bone, found by researchers in the 1970s. Scientists have now finally confirmed that the bone matches that of a fossilized Gastornis of similar age found in Wyoming.

“I couldn’t tell the Wyoming specimens from the Ellesmere specimen, even though it was found roughly 4,000km (2,500 miles) to the north,” said Prof Thomas Stidham of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. Stidham and his colleague Jaelyn Eberle, of the University of Colorado Boulder, matched the bones through techniques such as studying where muscle attachments lay. The research has been published in Scientific Reports.

The research raises some interesting questions over the behavior of Gastornis. The giant bird may have migrated south during winters in the Arctic, where darkness envelops the region for months at a time. The species was originally thought to be a formidable carnivore but recent research suggests that Gastornis was probably a vegan, using its huge beak to munch through leaves, nuts, seeds and fruit.

Eberle said bird fossils found in the Arctic are “extremely rare” and that the researchers aren’t sure whether Gastornis lived in the area year round.

“There are some sea ducks today that spend the winter in the cold, freezing Arctic, and we see many more species of waterfowl that are only in the Arctic during the relatively warmer spring and summer months,” she said.

Canada’s Ellesmere island is the 10th largest island in the world and lies adjacent to Greenland. Riven with fjords and attached to vast aprons of ice, Ellesmere is one of the coldest, driest and most remote places on Earth. Temperatures can reach -40C (-40F) in winter.

It was a very different place 53m years ago, however, during the Eocene epoch. During this time, Antarctica was still attached to Australia and global temperatures were unusually warm, which meant the world was mostly ice-free. Ellesmere island would have been covered in the sort of cypress swamps now found much farther south in the US, with evidence that the area hosted turtles, alligators, primates and even large hippo-like and rhino-like mammals.

While apes and alligators won’t be returning to Ellesmere any time soon, the researchers said that the discovery of Gastornis provided a better understanding of the consequences of a changed climate.

“Permanent Arctic ice, which has been around for millennia, is on track to disappear,” Eberle said.

“I’m not suggesting there will be a return of alligators and giant tortoises to Ellesmere island any time soon. But what we know about past warm intervals in the Arctic can give us a much better idea about what to expect in terms of changing plant and animal populations there in the future.”

.webp)

.webp)